Episodes

Episodes

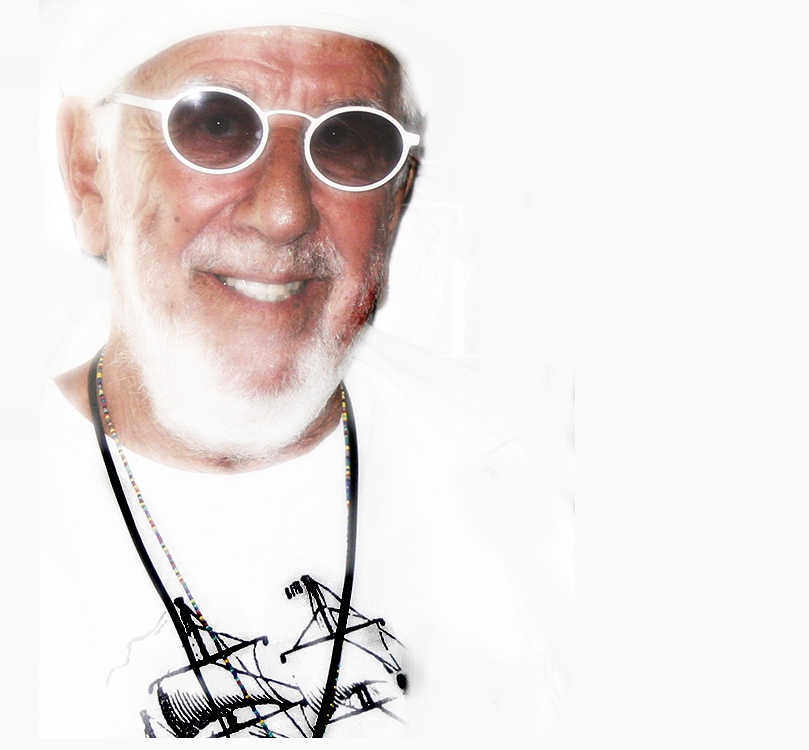

Episode 9. Chris Difford

He’s most famous for being half of the great Difford-Tilbrook songwriting duo of Squeeze, a collaboration born more than four decades ago in Blackheath, England, and which has generated a thick songbook of infectiously sophisticated pop rock storytelling, from “Pulling Mussels from a Shell,” through “Black Coffee In Bed,” “Cool for Cats,” “Annie Get Your Gun” and so many more.

It’s a collaboration that was initially sparked by Difford and his delight in telling stories. With five stole pence from his mother, he posted a card in the tobacconist’s window seeking a guitarist. A band about to get a record deal and go on tour, it said, had a guitarist slot needing to be filled. Although this was entirely a fabrication, it worked. Only one musician answered, but that was enough. It was Glenn Tilbrook.

”It was a complete bluff,” Difford said in a 1999 interview, “I was just lonely, looking for a friend.”

Tilbrook said it was Difford’s stated influences which caught his attention. “Chris put down Kinks Glenn Miller and Lou Reed,” said Tilbrook. “I thought that was interesting.” Also interesting was Difford’s spy-novel instructions for their first meeting: “Meet me at the Three Tuns in Blackheath village at six o’clock. I’ll be carrying a copy of the Evening Standard under my arm.” When Tilbrook arrived he met a long-haired young man in a lurex coat of many colors, with the Evening Standard under his arm. “Why he didn’t just tell me about the coat,” Tilbrook said, “I’ll never know.”

But that mystery was quickly supplanted with delight when he first encountered the vivid, mythic tales Difford told in song, and with a distinctive linguistic flair and grace. Though Glenn had been writing both words and music to his own songs up to then, soon as he realized the expanse of Difford’s abilities, he left the lyrics to him.

“I felt tremendous admiration for his lyrics,” said Tilbrook, “which outstripped anything that I was capable of. The first things he showed me were like Jacques Brel songs – tales of sailors and whores, the like of which I’d never heard before. He had, and has, a turn of phrase that leaps out of the page. Within two or three times of meeting up, we felt we would like to try and write together.”

D

D

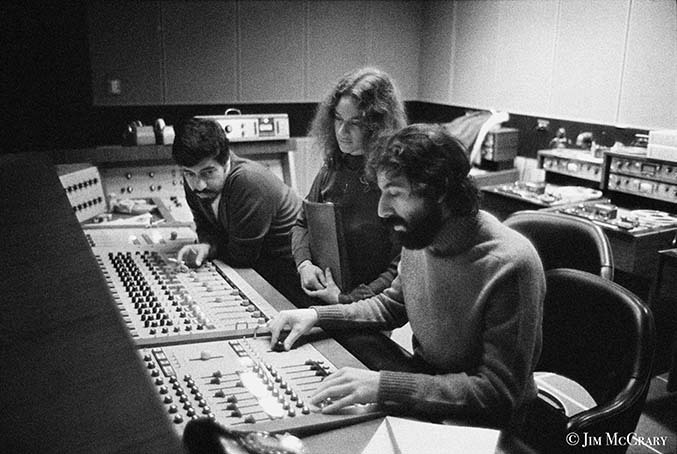

Difford & Tilbrook.

Their very first song was called “’Hotel Woman.” It wasn’t particularly great,” said Tilbrook, “but it defined our roles straight away. I took over the musical side and Chris took over the lyrical side exclusively.”

They also started performing their music. Unlike Bernie Taupin with Elton, who wrote words but never performed them, Chris was a part of the band. Since his voice is naturally low, he and Tilbrook never sang harmony, they sang in unison an octave apart.

They wrote a lot of songs before they started Squeeze, for about three years, during all incarnations of the band, and also after Squeeze, for their Difford-Tilbrook project and for other artists such as Elvis Costello, Helen Shapiro and Billy Bremner. He also wrote songs for his own solo albums, started in 2003 with I Didn’t Get Where I Am.

In 2017, he published his autobiography, Some Fantastic Place: My Life In and Out of Squeeze.

Twice the recipient of the UK’s most prestigious songwriting award, the Ivor Novello Award, Difford also has famously shared his wisdom and love of songwriting in an annual songwriting retreat at Pennard House in Somerset. Songwriters from all around the world attend, including our own Louise Goffin, who recorded this interview there at the retreat, and shares the following about her friend Chris.

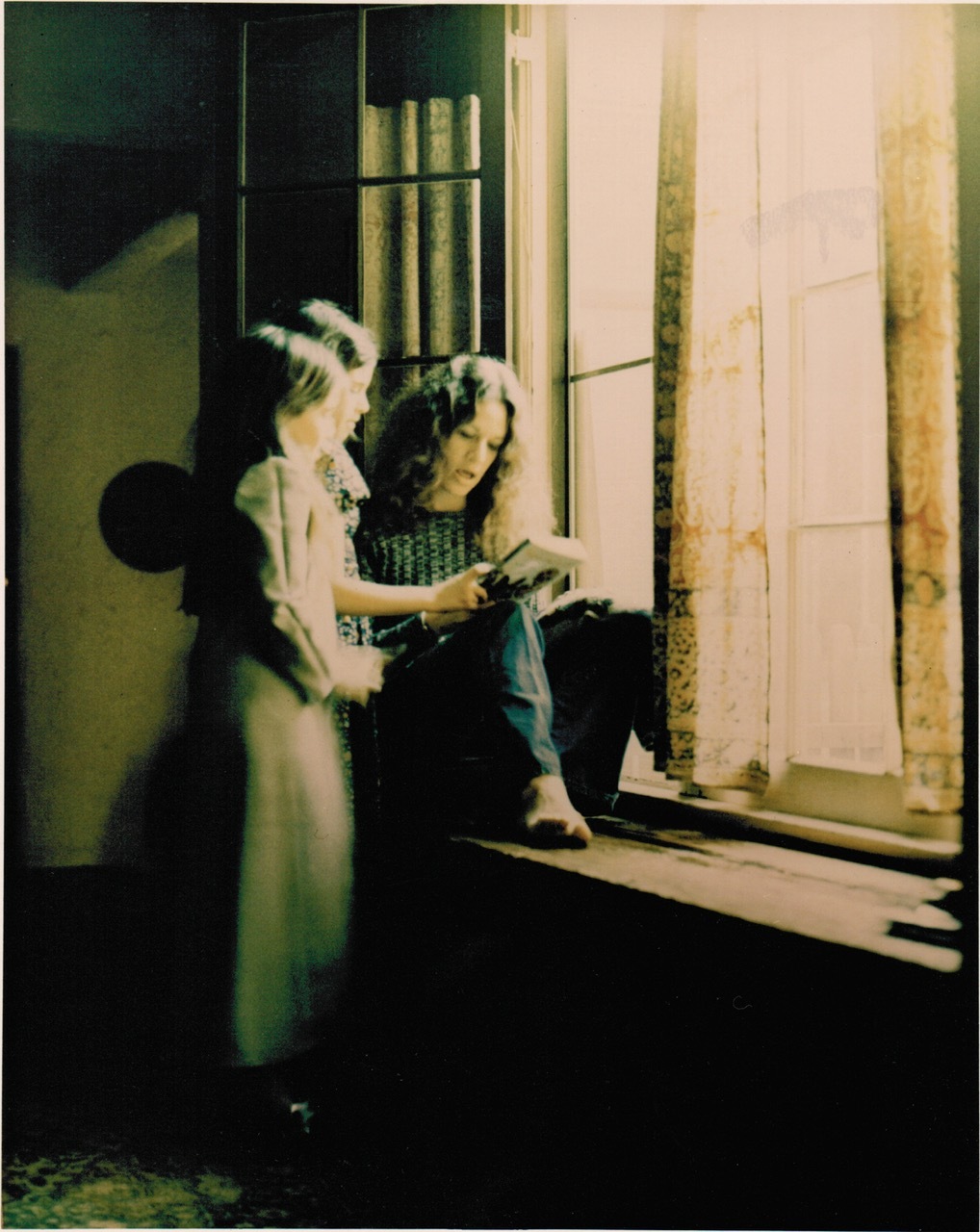

Chris & Louise

LOUISE GOFFIN: When I was 24 years old I was invited to come to London for ten days by Dave Robinson of Stiff Records to meet with producers about making an album for Stiff. It was mid-December and it was a rare winter in that it snowed on the streets of London that year.

There was something magical about the anonymity of spending the holidays in West London where I didn’t know a soul. I felt like it was the beginning of my adulthood, finding my own sandbox in the world. I kept extending my stay. Eventually ten days became ten years a Londoner! My first email address was “anexile.”

It was definitely a great song adventure. I’d take the tube to Chiswick to Dave Robinson’s office. He was running Island Records that year for Chris Blackwell and Stiff Records was also run from the same office.

After a few months of restlessness, bursting at the seams to collaborate, I heard from Dave Robinson’s wonderful assistant, Annie Holloway, who said, “You and Chris Difford ought to write some songs together.”

I thought, “You mean that could happen?” I must be doing the right thing staying in the UK because things were looking up. “I can write with Chris Difford?”

I think it was February that I took a bus down south to Blackheath where Chris invited me, and there was rain whipping at the bus windows the whole journey. Conversing with locals on the bus they would ask, “Where are you from?” And when I said California, with shock they’d ask, “What on earth are you doing here in this dreadful weather?”

Chris gave me lyrics about a Blue Guitar, one about the Algonquin Hotel, and another was words he’d written to music I had, for which I only had the title “Can’t Trust A Memory.” I’d have to dig deep into boxes of cassettes and pages to find them. That’d be a worthy scavenger hunt.

Shooting the video for “Paris, France” in England.

As it happened, a mere twenty-four years went by before Chris and I reconnected (over the internet) and another eight years for me to get to one of his songwriting retreats. Both figuratively and actually, we met again in person for much sunnier days. I was making an album, one I consider my best so far, and he had been hosting and facilitating Chris Difford’s Songwriting Retreats for twenty-five years in a row.

I remember saying to him, “Chris you seem so much sunnier than when we first met.” He said his journey of recovery may have had something to do with it. I feel honored to have been part of the abundance Chris has created with his songwriting retreats and the community that surrounds it. And simply joyous and grateful that I had the opportunity to sing a duet with him.

This last June, I went back for my second songwriting retreat and wrote so many good songs I went straight to adding them to my live set, skipping the recording part. But it is more than songs that I take home from his retreats. The newfound friends and shared experiences are enriching for years beyond the mere four days all the songwriters are gathered together. I felt lucky that Chris managed to set aside a little time in the hustle and bustle of the retreat to talk to me about his songwriting process, how he’s managed to sustain a four-decade-plus professional relationship with Glen Tilbrook, and his love of cross-pollinating creative skillsets.

EPISODE 9

Chris Difford

He’s most famous for being half of the great Difford-Tilbrook songwriting duo of Squeeze, a collaboration born more than four decades ago in Blackheath, England, and which has generated a thick songbook of infectiously sophisticated pop rock storytelling, from “Pulling Mussels from a Shell,” through “Black Coffee In Bed,” “Cool for Cats,” “Annie Get Your Gun” and so many more.

It’s a collaboration that was initially sparked by Difford and his delight in telling stories. With five stole pence from his mother, he posted a card in the tobacconist’s window seeking a guitarist. A band about to get a record deal and go on tour, it said, had a guitarist slot needing to be filled. Although this was entirely a fabrication, it worked. Only one musician answered, but that was enough. It was Glenn Tilbrook.

”It was a complete bluff,” Difford said in a 1999 interview, “I was just lonely, looking for a friend.”

Tilbrook said it was Difford’s stated influences which caught his attention. “Chris put down Kinks Glenn Miller and Lou Reed,” said Tilbrook. “I thought that was interesting.” Also interesting was Difford’s spy-novel instructions for their first meeting: “Meet me at the Three Tuns in Blackheath village at six o’clock. I’ll be carrying a copy of the Evening Standard under my arm.” When Tilbrook arrived he met a long-haired young man in a lurex coat of many colors, with the Evening Standard under his arm. “Why he didn’t just tell me about the coat,” Tilbrook said, “I’ll never know.”

But that mystery was quickly supplanted with delight when he first encountered the vivid, mythic tales Difford told in song, and with a distinctive linguistic flair and grace. Though Glenn had been writing both words and music to his own songs up to then, soon as he realized the expanse of Difford’s abilities, he left the lyrics to him.

“I felt tremendous admiration for his lyrics,” said Tilbrook, “which outstripped anything that I was capable of. The first things he showed me were like Jacques Brel songs – tales of sailors and whores, the like of which I’d never heard before. He had, and has, a turn of phrase that leaps out of the page. Within two or three times of meeting up, we felt we would like to try and write together.”

D

Difford & Tilbrook.

Their very first song was called “’Hotel Woman.” It wasn’t particularly great,” said Tilbrook, “but it defined our roles straight away. I took over the musical side and Chris took over the lyrical side exclusively.”

They also started performing their music. Unlike Bernie Taupin with Elton, who wrote words but never performed them, Chris was a part of the band. Since his voice is naturally low, he and Tilbrook never sang harmony, they sang in unison an octave apart.

They wrote a lot of songs before they started Squeeze, for about three years, during all incarnations of the band, and also after Squeeze, for their Difford-Tilbrook project and for other artists such as Elvis Costello, Helen Shapiro and Billy Bremner. He also wrote songs for his own solo albums, started in 2003 with I Didn’t Get Where I Am.

In 2017, he published his autobiography, Some Fantastic Place: My Life In and Out of Squeeze.

Twice the recipient of the UK’s most prestigious songwriting award, the Ivor Novello Award, Difford also has famously shared his wisdom and love of songwriting in an annual songwriting retreat at Pennard House in Somerset. Songwriters from all around the world attend, including our own Louise Goffin, who recorded this interview there at the retreat, and shares the following about her friend Chris.

Chris & Louise

LOUISE GOFFIN: When I was 24 years old I was invited to come to London for ten days by Dave Robinson of Stiff Records to meet with producers about making an album for Stiff. It was mid-December and it was a rare winter in that it snowed on the streets of London that year.

There was something magical about the anonymity of spending the holidays in West London where I didn’t know a soul. I felt like it was the beginning of my adulthood, finding my own sandbox in the world. I kept extending my stay. Eventually ten days became ten years a Londoner! My first email address was “anexile.”

It was definitely a great song adventure. I’d take the tube to Chiswick to Dave Robinson’s office. He was running Island Records that year for Chris Blackwell and Stiff Records was also run from the same office.

After a few months of restlessness, bursting at the seams to collaborate, I heard from Dave Robinson’s wonderful assistant, Annie Holloway, who said, “You and Chris Difford ought to write some songs together.”

I thought, “You mean that could happen?” I must be doing the right thing staying in the UK because things were looking up. “I can write with Chris Difford?”

I think it was February that I took a bus down south to Blackheath where Chris invited me, and there was rain whipping at the bus windows the whole journey. Conversing with locals on the bus they would ask, “Where are you from?” And when I said California, with shock they’d ask, “What on earth are you doing here in this dreadful weather?”

Chris gave me lyrics about a Blue Guitar, one about the Algonquin Hotel, and another was words he’d written to music I had, for which I only had the title “Can’t Trust A Memory.” I’d have to dig deep into boxes of cassettes and pages to find them. That’d be a worthy scavenger hunt.

Shooting the video for “Paris, France” in England.

As it happened, a mere twenty-four years went by before Chris and I reconnected (over the internet) and another eight years for me to get to one of his songwriting retreats. Both figuratively and actually, we met again in person for much sunnier days. I was making an album, one I consider my best so far, and he had been hosting and facilitating Chris Difford’s Songwriting Retreats for twenty-five years in a row.

I remember saying to him, “Chris you seem so much sunnier than when we first met.” He said his journey of recovery may have had something to do with it. I feel honored to have been part of the abundance Chris has created with his songwriting retreats and the community that surrounds it. And simply joyous and grateful that I had the opportunity to sing a duet with him.

This last June, I went back for my second songwriting retreat and wrote so many good songs I went straight to adding them to my live set, skipping the recording part. But it is more than songs that I take home from his retreats. The newfound friends and shared experiences are enriching for years beyond the mere four days all the songwriters are gathered together. I felt lucky that Chris managed to set aside a little time in the hustle and bustle of the retreat to talk to me about his songwriting process, how he’s managed to sustain a four-decade-plus professional relationship with Glen Tilbrook, and his love of cross-pollinating creative skillsets.